He was a droopy-eyed old timer, heavy around the middle, and when he strained in his folding chair to make change or rearrange his buckets you could see he had something wrong with one of his legs. But that didn’t prevent him from making serious eye contact with potential customers while bellowing like a beer vendor at Fenway Park.

“Don’t make me hollah, they’re only a dollah!” he would boom as I and hundreds of other commuters trudged past him to board our trains home. He was selling flower bouquets for a buck, and they were just the right size to carry on the train. Since he set up his cart at the main walkway to the platforms every weekday afternoon, anyone boarding a train had to walk right past him.

In the 1980s I walked by that guy most weekdays for almost five years, and I bought plenty of flowers from him, but I was young and preoccupied with my own issues so I never gave much thought to him or his business—and then I moved away. But recently, while planning a lesson on competition and competitive strategy, I started thinking about him and his business once again.

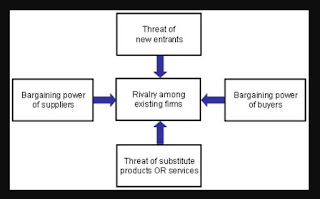

If you have studied economics at all, you probably know about Michael Porter and the work he has done on industry competition, particularly his “five forces” of competition model. You can watch him talk about that model here, but basically, Porter's five forces include competition from established and known rivals, new or emerging rivals, the threat of substitute products or services, as well as threats tied to the bargaining power of suppliers and customers. The weaker the forces, the more attractive the industry in terms of profitability.

As I remember it, the flower seller at North Station had no rivals on-site other than a more traditional flower shop inside the B&M terminal which offered a larger assortment of flower arrangements at much higher prices. I have no idea how he secured what seemed to be the exclusive right to sell flowers near the walkway to the train platforms, or why other competitors didn’t try to enter that space. Maybe he had competitors originally but drove them out of the market with low prices and superior location. Or maybe he had a special flower vendor’s license that was no longer available to potential competitors. I don’t know where he got his flowers, but I remember the wholesale flower exchange was not far away from the train station.

His sales transactions were quick, his product inexpensive. Impulse purchases were accommodated effortlessly--a commuter running for a train who decided to buy flowers from him could do so almost without breaking stride since he had just one price and he only accepted cash. Factor in the convenience and social usefulness of being able to purchase flowers at the last minute, particularly on birthdays, anniversaries and holidays, and it’s not hard to understand why buyers didn’t try to negotiate purchase prices with him.

I don’t have all the details, of course, but at least in my memory that flower vendor seemed to be operating in an ideal market featuring weak forces of competition, steady product supply, reliable and predictable product demand, low price sensitivity and the opportunity to make a profit. In other words, he was one lucky flower vendor! He had no real competition, so he didn’t need to worry about sources of competitive advantage, but I am sure he had a value proposition in his head built around what benefit he provided, to whom, and how he provided it better than anyone else. Using Geoffrey Moore’s template (from Crossing the Chasm) to outline his value proposition, I imagine it might have been something like this:

|

Value Proposition

| ||

| For | Target Customer | B&M Railroad commuters at North Station, Boston |

| Who | Need or Opportunity |

who want to bring flowers home as a surprise, or gift, or symbol of love and affection

|

| Our | Service/Category | we are the only flower stand directly on the walkway to the trains |

| That | Statement of Benefit | and we offer a wide selection of fresh flower arrangements—quick, one low cost, no waiting. |

The good news is that after reminiscing for a while I was able to include the flower vendor scenario as a case study in the lesson I was developing. The bad news is that my efforts to get additional details about him came up empty. I’d still like to know which of Porter’s five forces of competition eventually impacted his business, when, and how, and what he did to manage them.

I plan to keep digging, but if you (or someone you know) commuted by train from Boston’s North Station in the late 1980s, please send me an email (dean.harring@gmail.com) describing whatever you remember about that flower seller, his competitors, and the North Station marketplace in which he operated. It would be great to know the rest of his story.

Dean K. Harring is a retired executive who now enjoys his time as an advisor, board member, educator, and watercolor painter. He can be reached at dean.harring@gmail.com or through LinkedIn or Harring Watercolors